$3.25M NIMH grant will support threat computation study

Boston College’s Psychology and Neuroscience department has received a five-year, $3.25 million grant from the National Institute of Mental Health to study previously overlooked brainstem threat computation, potentially yielding essential data for the development of effective anxiety disorder treatments intended to reduce unwarranted fear.

Investigators have been studying neural circuits as a threat source for approximately 50 years, explained Associate Professor Michael A. McDannald, but the human brainstem has been ignored as a source of threat computation and a dysfunction site for disorders.

“Our work will reveal threat signaling, prediction error computation, and specific fear behavior organization by brainstem networks — knowledge that is crucial to the advancement of therapies to treat severe, ongoing anxiety that interferes with a persons’ daily activities,” said McDannald, the study’s principal investigator, who heads the department’s McDannald Lab. “Fear in the face of danger is healthy, and helps us prevent harm. However, fear when a threat is unlikely, or when we’re actually safe, is detrimental to our well-being, and is central to anxiety disorders.”

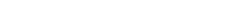

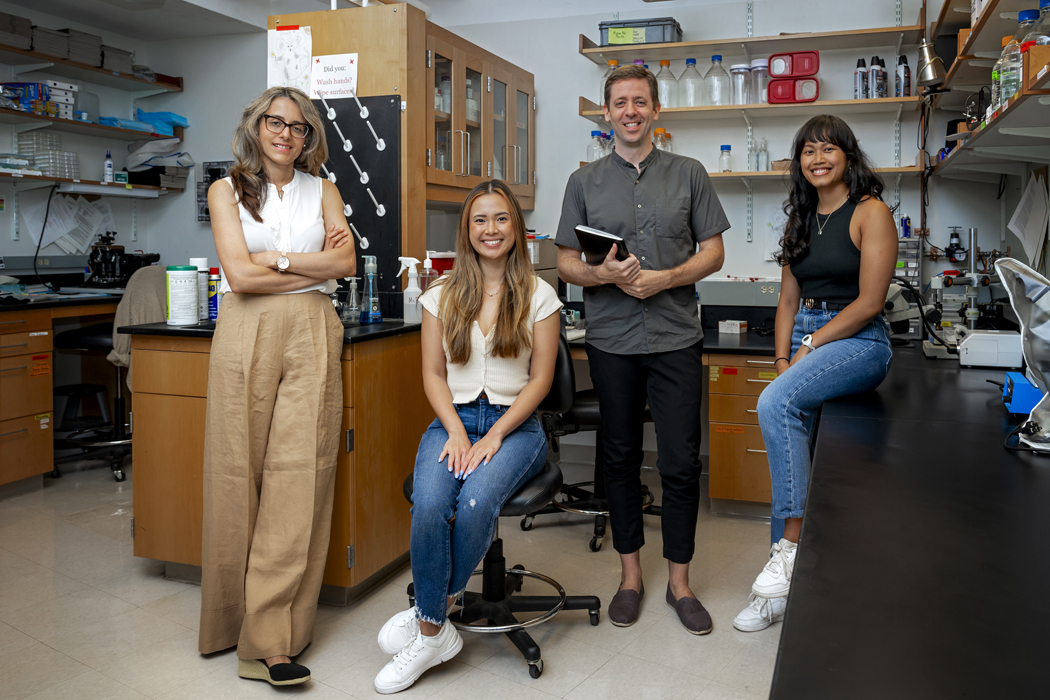

Michael McDannald with project co-investigators: (l-r) postdoctoral fellow Mahsa Moaddab and graduate students Amanda Chu and Emma Russell. (Caitlin Cunningham)

Co-investigators include postdoctoral fellow Mahsa Moaddab, and graduate students Amanda Chu and Emma Russell. The grant is effective immediately.

“This new grant further bolster’s our department’s longstanding interests in elucidating how individuals figure out what is good or bad, or safe or dangerous, in the world,” said Elizabeth A. Kensinger, professor and chair, department of Psychology and Neuroscience. “We are extremely fortunate to have faculty like Michael McDannald bringing cutting-edge neuroscience methods to bear on this important topic.”

According to the National Alliance on Mental Illness, anxiety disorders are the most common mental health concern in the United States. Over 40 million adults — approximately 19 percent of the population — suffer from an anxiety disorder, while approximately seven percent of children ages 3-17 experience issues with anxiety each year. Most people develop symptoms before age 21.

Occasional anxiety is normal, noted McDannald; people inevitably worry about health, money, or family problems, but anxiety disorders, such as panic disorder, social anxiety, and various phobia-related conditions involve more than temporary apprehension or fear. For people with an anxiety disorder, the angst does not disappear and can worsen over time, frequently affecting job performance, schoolwork, and relationships.

“The ultimate goal of our research is a world in which everyone can experience healthy fear,” said McDannald.