Originally published in Carroll Capital, the print publication of the Carroll School of Management at Boston College. Read the full issue here.

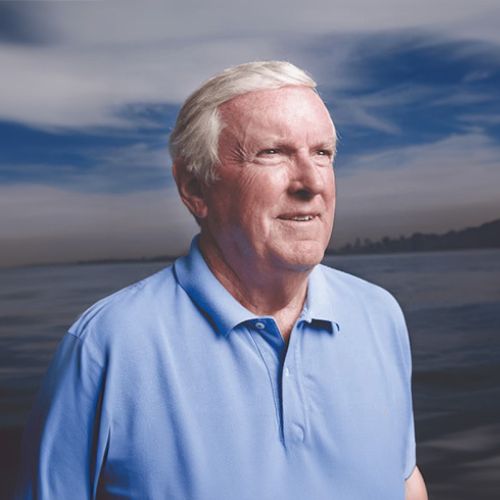

Inside a tiered lecture room in Higgins Hall, Carroll School of Management professor and Nobel laureate Paul Romer is speaking at a gathering of physicists and peppering his lecture with terms of art that they’d know well, like “convexity,” a mathematical property featuring tangent lines on a graph. The renowned economist is plotting out theories of growth that trace back to physics, including the relationship between inputs and outputs of energy. Minutes into the lecture, a professor in the front row interrupts Romer, challenging the idea that if you double all of the inputs (say, the people, land, and tractors), you’ll double the outputs (food for those people). The objections continue, and a few of the professor’s colleagues try to shush him. But Romer, the Seidner University Professor who directs Boston College’s new Center for the Economics of Ideas, is unperturbed. He’s clearly enjoying the give-and-take, and he salutes his interlocutor. “He’s showing me respect,” Romer tells the colleagues. “This is how you show respect—you disagree. You engage.”

%20.jpg)

The whole scene, not just the exchange but the curiosity of an economist floating into the orbit of physicists, begins to sketch a portrait of Romer the scholar. For one thing, he doesn’t sit comfortably in his own discipline, chiming with the preferred ways of understanding people and economies. He isn't sitting at all in an economics department; he’s a finance professor at a school of management. To be frank, Romer isn’t resting easily at the Carroll School either. Though he has tossed himself into the daily stir of a top-ranked finance department, he keeps popping up in disparate places on the Heights, discoursing with political scientists on the nature of citizenship in a globalized world; hanging with the physicists in Higgins; back in Fulton, presenting his research to a standing-room-only crowd of Carroll School faculty; and wending his way into other conversations.

The 2018 Nobel Prize winner in economics isn’t even teaching economics, or finance for that matter. His first course at Boston College this past spring was “Digital Self-Defense with Python,” a coding class (he taught himself Python in 2018 after a stint as the World Bank’s chief economist). Why is Paul Romer teaching coding to undergraduates? And why is he having so much fun being cross-examined at a physics colloquium?

It’s all about the ideas.

Romer won the Nobel for his “New Growth Theory,” which holds that knowledge and ideas are the key drivers of economic growth. Previous research had highlighted the role that technology plays in expanding the quantity and quality of goods and services, but Romer turned the accepted wisdom on its head, demonstrating the essential difference between physical objects and ideas. Basically, objects are subject to the laws of scarcity; as more people tap a new freshwater source in the developing world, for instance, there’s less of it to go around. On the other hand, ideas (which he likes to call “recipes”) are endlessly plentiful and reusable once they’re discovered.

One of his favorite illustrations is a bracingly simple idea concocted several decades ago in refugee camps in Bangladesh. Some medical personnel began mixing glucose, sugar, and a little water, and found that this recipe, in just the right amounts, would cure children suffering from deadly dehydration. Since then, the solution has saved millions of lives in poor nations, because ideas are replicable. The life-saving idea of oral rehydration therapy could be used over and over, at scarcely a cost and administered by parents in their own homes.

At the Carroll School’s Finance Conference two years ago, Romer spoke of such breakthroughs as he brushed aside a national mood of pessimism. “Throughout history, things get better and better, and they get better faster and faster. People come up with ideas that give us so many ways to do more with less,” he said. “It’s not even remotely possible that we’ve run out of new things to discover.” This is vintage Romer optimism, and yet, the proclaimer of economic progress has been raising alarms that have grown more urgent. He talks about what he sees as a business culture in which lying and deception have been normalized, about increasingly untrustworthy digital messages that hamper the flow of ideas, and other trends that would derail the train of human progress. Romer, the acclaimed optimist, is worried.

%20.jpg)

During an interview in his fifth-floor Fulton Hall office, he wants to make it clear that his optimism has always been a product of empirical evidence, not so much his personality. “I don’t have a naturally sunny disposition,” says Romer, who keeps a fairly steady look on his face, at times wearing a slight grimace, at times offering a strong suggestion of a smile. He cuts a striking figure with his mane of pearly white hair, dark brows, and black-framed glasses.

Growing up in Denver, Romer could see the world as a friendly place. He lived in a tree-lined city neighborhood with squads of kids playing kickball on the streets. His father, Roy, was a lawyer, small business owner, and politician who eventually became Colorado’s governor; his mother, Beatrice, an advocate of early childhood education who, as first lady, spearheaded Colorado’s statewide preschool program. They had seven children. “We weren’t wealthy, but we were fortunate. Our parents created an environment for learning, exploring, and developing a taste for understanding the world,” Romer recalls. He spent summers in the mountains outside Denver, working on his father’s ranch and tending to horses and cattle.

It was, though, the 1960s, and the wider world was convulsing with protests and assassinations. The upheavals hit home for Romer when his father, after losing a US Senate election as the Democratic Party’s nominee in 1966, was ostracized by his party for opposing the Vietnam War. Rather than backtrack, Roy Romer chose to leave politics, a decision that made a lasting impact on his son, 11 years old at the time. Paul Romer says the lesson was: “If you reach a point in your career where you feel you have to compromise to continue on the path you’re on, just change the path.” His father returned to politics a decade later, when he became secretary of agriculture in Colorado; he served as governor from 1987 to 1999.

“ Throughout history, things get better and better, and they get better faster and faster. People come up with ideas that give us so many ways to do more with less. It's not even remotely possible that we've run out of new things to discover. ”

In a way, family history repeated itself during the 1990s. Paul Romer wasn’t exiled from academia, but he says the prevailing winds—blowing, notably, from economics professors at the University of Chicago, his undergraduate and Ph.D. alma mater—were complicating his path to publication. Some influential economists were throwing cold water on his findings about the growth effects of ideas.

“I got to a point where my voice couldn’t be heard. I couldn’t get the word out through traditional journals,” he says. “I hit a roadblock and was forced to either compromise or go do something else.” Applying his father’s lesson, Romer chose to leave the economics profession and stake out new passions. In 2001, he founded an educational technology company, Aplia, which created online exercises to reinforce classroom learning; he sold the company to Cengage Learning six years later. After that, Romer turned to urbanization, launching the concept of Charter Cities, newly created municipalities in the developing world. He became founding director of New York University’s Marron Institute for Urban Management.

Asked if he felt vindicated by the Nobel Prize, Romer says, “What would make me feel vindicated is if people were more willing to engage with the general questions I’ve been asking.”

Does this mean that economists were unswayed by his growth theory? Hardly, says Michael Kremer, who won a Nobel Prize in 2019 for his research on development economics in lower-income nations. “Paul’s work sparked an explosion in research on economic growth in the ‘90s. I think his work was widely appreciated very rapidly,” says Kremer, now teaching at the University of Chicago. He adds that Romer’s insights “form the core” of how economists today think about growth.

Chad Jones, a Stanford University economist who built his own ideas on Romer’s foundation, says Romer “relaunched the whole field of growth” that had languished for decades, but he points out that it’s hard to change the world twice, and Romer’s subsequent work on growth attracted less interest after his groundbreaking 1990 paper. Jones says it’s partly because Romer “didn’t play the academic game”—for one thing, he wrote in a less technical style than other economists. The Stanford professor also notes that some of Romer’s closest and most prominent colleagues at the University of Chicago didn’t buy into his growth theory, which might have, to an extent, tilted the publishing decisions of some top journals. Romer’s sober assessment is that economists overall have gone from ignoring the role of ideas to making it merely a “footnote” in their work.

.jpg)

Romer often says that management professors have been perhaps his most engaged audience, owing to the implications of his research for innovation driven by ideas. One of those academics was Peter Drucker, the father of modern management theory. Another was the Carroll School’s John and Linda Powers Family Dean, Andy Boynton, who first connected with Romer by email in the early 1990s.

In 2011, Romer wrote a blurb for Boynton’s book The Idea Hunter: How to Find the Best Ideas and Make Them Happen, co-authored by Bill Fischer; they argued a la Romer that a shortage of ideas inhibits innovation much more than a shortage of things. The Boynton-Romer connection continued with the invitation to address the 2022 Finance Conference, after which the dean recalls asking him, “Would you ever consider working here?” Romer replied, “I might.” After numerous conversations with Boynton and University Provost David Quigley, Romer arrived at the Carroll School in fall 2023, the first Nobel laureate to serve on Boston College’s permanent faculty. He commutes weekly between Chestnut Hill and New York’s Greenwich Village, where he lives with his wife, Caroline Weber, and their five dogs.

Notwithstanding his forays beyond Fulton, Romer has embedded himself in the Finance Department, attending lunch conversations, mentoring junior faculty, and participating in interviews with prospective faculty, who are often surprised to see him. “He’s already made an impact on our department,” says Professor Ronnie Sadka, department chair and senior associate dean for faculty. “He’s very interpersonal, very approachable.”

For his part, Romer calls Boston College “a place where people care about integrity and values. It’s part of why I like the intellectual community here.” It also meshes with his mounting concern about companies, especially tech, which “adopt business models that involve dishonesty, misrepresentation, and exploitation of the customers,” he says. “They feel they’re in these winner-take-all contests where they have to win at any cost or die. And once they win, even if they’ve damaged their reputation, they’re dominant. They’ve cornered the market.”

During an interview in April, he cited a plethora of examples, including headlines that day about Google agreeing to destroy billions of data records to settle a lawsuit that claimed it secretly tracked people’s private browsing, even though the company had earlier said it would be impossible to destroy the data. Romer acknowledges that it’s hard to produce data on something as nebulous as an increase in dishonesty, but of course we’re talking about someone with a history of bringing dimly lit truths out of the haze.

On a raw and rainy night in April, Romer is setting out for his coding class, which will take up ways of authenticating digital transmissions. This isn’t theoretical for Romer, whose X (Twitter) account was impersonated with a slightly tweaked handle in 2023; the fake Romer messaged some of the followers, inviting them to invest in a dubious crypto-currency fund. (Now off social media, Romer continues to blog at paulrommer.net). “It could be a social media message, an email, a spreadsheet, whatever,” he explains while taking the stairs four floors down to class. “You can’t trust anything unless you know who’s the person who vouches for it, someone who has a track record of being reliable. You can’t trust the content inside those messages.” His solution, easier said than done, is for the sender to put a “digital signature” on the message that the recipient can verify, which reveals the sender’s identity and ensures that no one has tampered with the message.

“ I don't think anyone really needs to be anonymous. You wouldn't trust someone who insisted on meeting with you in a gorilla mask, not wanting to tell you who they are. And you shouldn't want that digitally either. ”

This is his ambitious project as founding director of the Center for the Economics of Ideas, where Romer, with help from Business Analytics Professor Sam Ransbotham, is working on practical solutions. The chief goal is to develop user-friendly software that would enable any reader to sign and verify files they receive; he’s testing out the software partly by having students work on prototypes. But as Romer begins discussing authentication during class, he gets pushback from some students who want to keep open the possibility of anonymity, which a digital signature would undo. One young man remarks that whistleblowers, for example, need to be anonymous “or else they’re vulnerable to attack.” Romer responds that false accusations by trolls and nameless whistleblowers have become a worrisome trend in academia and other circles.

“I don’t think anyone really needs to be anonymous,” he says. “You wouldn’t trust someone who insisted on meeting with you in a gorilla mask, not wanting to tell you who they are. And you shouldn’t want that digitally either.” But the students—members of the digital generation—seem at ease with the gorilla masks.

For all his concerns (including what he sees as a growing disconnect between corporate power and social benefit), Romer’s empirical optimism remains intact. He always returns to the possibilities of progress and the endless discoveries waiting to happen. That confidence comes through in his moonshot for digital authentication, which takes on fuller significance when you consider how critical digital messaging is to research and the transmission of ideas that propel growth.

Romer’s new mission will surely invite skepticism, but his dean says it would be foolish to underestimate him. “He’s changed the world once with his discoveries about ideas and growth,” says Boynton. “Can he do it again, in the digital sphere? I’m betting on it.”