History

In the early part of the 20th century the big event for Boston College and the Fulton Debating Society was the move to Chestnut Hill, where the college swelled with pride in its magnificent new building and the Fulton men gloried in the special amphitheater built for them. Father Gasson followed the example of Father Fulton in providing the debating society a room of its own—and what a room! The Boston College Club of Cambridge made a gift (the amount is unrecorded) specifically for the Fulton room, and all generations of Boston College people are in their debt for their role in creating one of the architectural gems of the campus.The ceiling of the room forms a Gothic arch, reflecting the building's architecture. The sloping ceilings on either side were, fittingly, adorned with six examples of or tributes to oratory: in Greek by Demosthenes, in Latin by Cicero, in Jerome's Latin rendition of St. Paul, in Italian by Paolo Segneri, S.J., in French by Louis Bourdaloue, S.J., and by Daniel Webster.

Three of the quotations are from secular and three from sacred eloquence. From the vantage of the platform in the Fulton room the quotations from Cicero, Webster, and Demosthenes are on the left wall and those from Segneri, St. Paul, and Bourdaloue on the right wall. The unknown selector of the quotations has provided generations of Fultonians with gems of eloquence and exhortation. They are called, as aspiring orators, to selfless patriotism, to respect for human dignity, to lofty life goals, to sincerity springing from high intellectual and moral force. Truly these are guidelines that challenge the mind and stir the heart.

Tributes to Oratory

The selection from the great Greek orator Demosthenes is taken from his speech, "On the Crown." The translation given here is from the Loeb Classical Library. The style is a bit old-fashioned, but that is perhaps appropriate to the time when the Greek was copied on the Fulton wall, with some wrong accents and erroneous letters, by Brother Schroen. Father David Gill, S.J., of the Department of Classical Studies, identified the selections from Demosthenes and Cicero in their respective works.

But it is not the verbal fluency of the orator, Aeschines, nor the stretch of his voice, that is valuable, but that he should choose the same ends as the bulk of his countrymen, and should hate and love the same persons as his country. For the man who has his soul thus ordered will say everything with loyal intentions; but the man who courts those persons from whom the city anticipates danger to herself, does not ride at the same anchor with the multitude, and consequently has not similar expectations of safety. But, mark you, I have; for I adopted the same interests as my hearers, and have done no isolated or individual act.

Cicero is represented by some lines from his treatise on the orator, DeOratore, Book I, viii, 32 and 34. Again the translation is from the Loeb Classical Library.

What function is so kingly, so worthy of the free, so generous, as to bring help to the suppliant, to raise up those that are cast down, to bestow security, to set free from peril, to maintain men in their civil rights? Not to pursue any further instances—wellnigh countless as they are—I will conclude the whole matter in a few words, for my assertion is this: that the wise control of the complete orator is that which chiefly upholds not only his own dignity, but the safety of countless individuals and of the entire state. Go forward therefore, my young friends, in your present course, and bend your energies to that study which engages you, that so it may be in your power to become a glory to yourselves, a source of service to your friends, and profitable members of the republic.

The most interesting of the citations from the point of view of writing this paper was that from St. Paul, because it took some literary sleuthing to discover that the selection is composed of thirteen excerpts from six of the Pauline letters. A translation is presented unannotated. . . .

Take strength, my son, from the grace which is ours in Christ Jesus. Stand by what you have learned and what has been entrusted to you, remembering from whom you learned it. Run the great race of faith; take hold of eternal life. Test everything; keep hold of what is good. Turn from the wayward passions of youth. Pursue justice, piety, integrity, love, fortitude, and gentleness. In everything set an example of good conduct: in your teaching, your integrity, your seriousness. Have nothing to do with supersititious myths, mere old wives' tales; keep yourself in training for piety. While the training of the body brings limited benefit, the benefits of piety are without limit, since it holds out promise not only for this life but also for the life to come. What you say must be in keeping with sound doctrine. Never be harsh with an older man; appeal to him as if he were your father. Treat younger men as brothers. Do not dispute about mere words; it does no good and only ruins those who listen. Be on the alert; stand firm in the faith; be valiant, take courage. Let us never tire of doing good, for if we slacken not our efforts we shall in due time reap our harvest.

A scripture scholar, Father Joseph Fitzmyer, S.J., Gasson professor at Boston College from 1987 to 1989, says he knows of no precedent for a concatenation of texts such as that from St. Paul in the Fulton room. He concludes, as we must, that some Jesuit on the Boston College faculty culled sentences from various passages of St. Paul, which fit together rather nicely, and described the new text correctly in the line below the inscription, "From the letters of St. Paul."

Paolo Segneri of the Society of Jesus is one of the great pulpit orators in the history of Italy. He flourished in the second half of the seventeenth century. The citation on the wall of the Fulton room is taken from his fourth sermon for the first Sunday in Lent. Thanks are given to Joseph Figurito of the Department of Romance Languages and to Father Patrick Ryan, S.J., of the Department of Theology for the translation from the Italian.

What food is for the body, the word of God is for the soul. "Cibus mentis est sermo Dei," says a disciple of Ambrose, and the common language of the saints echoes him. Nor is this surprising. The word of God preserves in the soul the spark of life so that it be not extinguished. It nourishes the soul when exhausted, strengthens it when weak, makes it robust when spent. Indeed this food has a wonderful advantage over every other kind of food. For every other food, however choice, however healthful, however substantial, can do nothing for our bodies unless they are alive. But the divine word calls back to life souls that are dead. So which of you would be surprised to hear that Christ affirmed that man does not live by bread alone but by every word that comes from the mouth of God? It can be said, not just metaphorically but really, that when the soul, the noblest part of man, is nourished by the word of God, the whole person is nourished by it.

Like Paolo Segneri, Louis Bourdaloue was a seventeenth century Jesuit and a premier pulpit orator. His reputation in France was perhaps ever greater than Segneri's in Italy. Whoever chose the selections from these two talented men again chose a lenten sermon. The Bourdaloue excerpt is from a sermon for the Second Sunday in Lent entitled, "On the wisdom and sweetness of God's law." Father Joseph Gauthier, S.J., of the Department of Romance Languages, kindly provided the translation.

God's law is at once a yoke and a comfort, a burden and a support. Didn't this law of love change shackles into bonds of honor? Witness a Saint Paul. Didn't it make the cross attractive? Witness a Saint Andrew. Didn't it give refreshing coolness in the midst of flames? Witness a Saint Lawrence. Doesn't it continue to perform countless miracles before our very eyes? If the law seems difficult to you, don't put the blame on the law or its burdens but on yourself and your indifference towards God. The law is difficult for those who fear it, for those who would like to change it, for those whom the spirit of God, the spirit of grace, the spirit of love doesn't quicken, doesn't embolden, doesn't touch because they don' t want to be touched. But let us take heart and with a holy desire to please God let us enter into the way of His commandments. We will stride, we will run, we will enjoy the blessed eternity to which we are being led.

The quotation from Daniel Webster is from a discourse, "Adams and Jefferson," delivered in Faneuil Hall, Boston on August 2, 1826. The two former presidents and friends died on the same day, the 50th anniversary of the republic, July 4, 1826. In the chosen excerpt Webster was speaking of the quality of John Adams' eloquence. Let Webster's words introduce the passage on the Fulton room wall: "The eloquence of Mr. Adams resembled his general character, and formed indeed a part of it. It was bold, manly, and energetic; and such the crisis required." He then continued:

When public bodies are to be addressed on momentous occasions, when great interests are at stake, and strong passions excited, nothing is valuable in speech farther than as it is connected with high intellectual and moral endowments. Clearness, force, and earnestness are the qualities which produce conviction. True eloquence, indeed, does not consist in speech. It cannot be brought from far. Labor and learning may toil for it, but they will toil in vain. Words and phrases may be marshalled in every way, but they cannot compass it. It must exist in the man, in the subject, and in the occasion. Affected passion, intense expression, and pomp of declamation, all may aspire to it; they cannot reach it. It comes, if it comes at all, like the outbreaking of a fountain from the earth, or the bursting forth of volcanic fires, with spontaneous, original, native force.

Postscript

Reprinted from Boston College Magazine, 2002

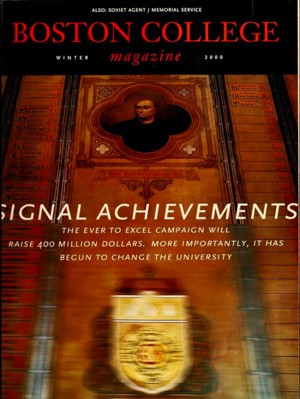

"You can naturally imagine how pleased I was to see my name [on] your Winter issue cover," wrote the author of a letter that reached our offices shortly after the Winter 2000 issue came out. The writer signed himself simply "- - - - '68." Thus began the trail toward the resolution of a 30-year-old Boston College mystery.

The photo on the Winter cover showed part of a wall in Gasson 305, where the names of the annual Fulton prize debate winners are painted on a long trompe l'oeil plaque.

In the spaces reserved for 1968, 1969, and 1970 there were no names, just dashes. Except for the years 1944-46, when World War II interrupted campus life, these were the only blanks on a roster of Fulton Prize winners stretching from 1890 to the present.

The mysterious note was passed on to John P. Katsulas, director of the Fulton Debating Society. A clue it contained--"[I] also won the medal twice"--proved inconclusive, so Katsulas set about solving the mystery of "- - - - '68" the old-fashioned way: with legwork. While at it, he decided to identify the other winners, as well.

Combing the Fulton archives, Katsulas came up with a list of likely prize-winners. He sent letters of inquiry, and a few months later he had his men.

Joining the ranks were, chronologically, David M. White '68; Mark Killenbeck '70; and Ronald Hoenig '70. (Hoenig didn't actually win the Fulton debate in 1970, but received the honor after antiwar protests led to the cancellation of all campus activities in the latter half of the spring semester.) The names have now been painted in their rightful spots.

According to Katsulas, Fultonians of the time trace the origin of the empty spaces to then Fulton director Bob Shrum's expanding political life. A speechwriter for John Lindsay in the 1969 New York mayoral campaign (and, since, for a string of politicians from George McGovern to Al Gore), Shrum "can't be blamed for letting it slip for a few years," says White.