Professor Kathleen Seiders (Marketing) noticed the referendums on business questions happening again and again—on food labelling, drug pricing, recycling, and many other issues. In each case, an industry invested millions of dollars, sometimes tens of millions, on ad campaigns to persuade the public to vote its way.

Kathleen Seiders

Seiders realized that marketing scholars knew little about how industries persuaded people in these direct-to-public campaigns or about what sorts of arguments worked and which didn’t. “This is something we don’t pay any attention to but that industries pay a lot of attention to,” she says. “Industries understand this is important, but it’s not clear the public understands the stakes.”

With one of her Carroll School marketing colleagues, Associate Professor Gergana Nenkov, and Andrea Godfrey Flynn of the University of San Diego, Seiders decided to change that.

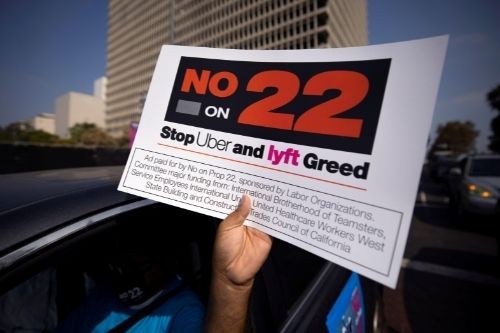

What they learned, published this spring in an article in the Journal of Marketing, helps make sense of a form of corporate “lobbying” that has been hiding in plain sight. It influences public policy across the United States but had been little examined by marketing researchers. And it clearly works because industries often win—as they did in 2020 in a landmark California ballot initiative on whether drivers for companies like Uber, Lyft, and DoorDash would continue to be treated as independent contractors.

Gergana Nenkov

In the California case, the referendum created a third classification of worker—independent contractors with limited benefits—that was sought by the ride-hailing-and-delivery industry, the so-called gig economy. (The limited benefits were a concession to labor advocates.) Had the measure failed, firms in the industry would’ve had to provide set wages and employee benefits to drivers and would’ve faced stricter regulation. According to The New York Times, gig-work companies together spent about $200 million to prevail in the vote.

“California is a precedent-creating battlefield for public policy,” says Seiders, who is also the new chair of the Carroll School's Marketing Department. The vote in favor of the gig-economy firms may discourage other states and even the U.S. Congress from trying to force them to treat workers as employees, she adds.

According to Seiders, Nenkov, and Flynn, strong arguments benefit both sides in these kinds of fights, though the activist side benefits more. Put differently, people aren’t dupes: they care about the quality of the arguments used to sway them.

At the same time, voters can easily become suspicious of activist arguments—which creates an opening for the industry side to gain an advantage by encouraging voter skepticism.

Which arguments work?

The professors also examined which sorts of arguments most help each side. What they found isn’t surprising, but it is enlightening when one considers how campaigns like these often play out.

Financial arguments work best for industries, they say. And that’s often what one sees in practice. In the California vote, for example, the industry claimed greater regulation would’ve raised companies’ costs and resulted in the loss of thousands of jobs.

In contrast, the activist side benefits from arguments that focus on societal welfare, the professors say. In California, opponents tried to win with such arguments in the battle over the industry-backed measure, Proposition 22, portraying a vote against it as advancing social justice. They said an anti-vote would help people of color, since these people were disproportionately represented among the drivers for the ride-hailing-and-delivery companies.

“Our results show that the fit between an argumentation strategy and the identity of the persuader is key, especially for the industry side,” the professors write.

What do the findings mean for campaigners on either side of votes like these?

Obviously, industry campaigns should lean to financial arguments, and activist ones to societal claims. But beyond that, the professors say industry succeeds when it aggressively attacks activist arguments to engender public skepticism. The activist side, for its part, must develop arguments with “ironclad strength” while “vigilantly preserving its legitimacy in reaction to any industry attacks,” the researchers write.

And how should voters evaluate each side’s claims? Nenkov says the research has made her more careful in her consideration of ballot initiatives.

“I used to spend about three seconds on how questions were framed on the ballot,” she says. “Now I try to do some research. A lot of ballot initiatives may seem like they’re good for consumers, but they may not be.”

She recalls a 2018 item in Massachusetts that would’ve limited the number of patients that each nurse in the state cared for. On first impression, it seemed as if it could’ve increased the quality of healthcare. Yet staffing decisions can require more flexibility than strict ratios allow, and the ratios might’ve raised healthcare costs. The measure ended up failing.

A critical factor in direct-to-public campaigns that the Carroll School professors didn’t examine is the truthfulness of arguments—they let their research subjects tell them how strong or suspicious arguments seemed without independently evaluating the veracity of the claims. That was by design, because truth is sometimes obscured or hard to guage in campaigns like these. Both sides are aiming to win, not inform.

“We can’t call this propaganda in the Journal of Marketing, but it is propaganda,” Seiders says. “It’s coming from both sides, and the intent is to persuade. It’s not to dwell on the truth of the matter or to tell people what’s really at stake.

“Look at what the tobacco industry did—they hoodwinked the public [about the risks of smoking], and they did that forever. They went right to the public to fight their battles, and it was very effective.”

Seiders has begun another research project that examines whether truthful arguments influence people more than untruthful ones.