Few illnesses lay bare the inequities of the modern global health system like tuberculosis. In 2021 alone, the disease killed 1.6 million people worldwide, more than any other infectious illness besides COVID-19.

These TB deaths, however, were concentrated in countries with high rates of poverty because most infections can be treated with antibiotics—and in wealthy countries, they have been for generations. This means that the failure to reduce the disease’s death rates globally isn’t a scientific problem: it’s a policy problem.

Brittney van de Water, associate professor at the Connell School of Nursing, hopes to better understand and address this inequity. She is studying approaches to implementing TB-care practices in order to discover which strategies actually work. “I wanted to look at the problem through an implementation science lens to be as effective as possible in the pursuit of global health equity,” van de Water said.

Out of a population of about 60 million, 450,000 South Africans develop TB each year. Of those, 270,000 are coinfected with HIV, and some 89,000 die annually, making the need for more effective care a critical matter of life and death. She explained that “almost every low-income country has a high incidence of TB, but in South Africa about 60 percent of tuberculosis cases are in people co-infected with HIV. That makes it a totally different and dangerous epidemic, and one that needs to be urgently addressed at a systems level.”

Assistant Professor Brittney van de Water Photo: Sophie Smith

The recipient of an R01 grant from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Nursing Research, van de Water will work to improve global TB care through her project “Using the Systems Analysis and Improvement Approach (SAIA) to Prevent Tuberculosis in Rural South Africa.” To figure out the most effective ways of delivering better care to people failed by the current system, van de Water is collaborating with clinicians and researchers in some of the most rural and impoverished parts of South Africa. Together, they’re looking to discover which public health interventions are failing—and which ones actually save lives.

The Obstacles

Rural South Africa is a challenging place in which to promote public health. Due in large part to the legacy of racial apartheid, many parts of the country had little to no access to schooling, infrastructure, or clean water until the mid-1990s. In the years since, development has remained slow and uneven, with many areas not receiving electricity until last year. Unsurprisingly, then, tuberculosis care remains heartbreakingly inadequate: only 80 percent of South Africans currently infected with TB receive a diagnosis, and just 53 percent successfully complete treatment.

Graphic: Christine Hunt

The prevalence of poverty and illness also inevitably changes the way clinicians care for patients. Van de Water said that her South African colleagues taught her two essential questions they ask when a patient presents at a hospital: “Where did you come from and how long did it take to get here? The answers to these questions reveal both how sick someone is and the startling realities of transportation for communities wrapped up in poverty.”

For example, if someone took a long time to cover a short distance, that tells the clinician something important about the patient’s current condition. This information also helps predict the likelihood of a follow-up visit—if a return is even possible when the rains come and turn dirt roads to mud.

But once a patient arrives at a hospital, the clinicians’ challenges have just begun. Even in hospitals achieving steadily better results on the other main challenges facing impoverished rural areas—HIV, maternal health, infant health—tuberculosis has been difficult to get under control. Sometimes this is because people with tuberculosis show up with symptoms for something else, so they don’t get screened for TB. And sometimes patients who are properly diagnosed are not able to follow the course of treatment because of food instability or lack of access to other essential resources.

Van de Water’s subject is not tuberculosis itself but TB care: at what stages in the treatment process are patients failed, and what barriers keep them from getting the care they need?

In short, van de Water explained, TB mortality rates remain stubbornly high—according to the WHO, untreated tuberculosis has a death rate of about 50 percent—because the global health community hasn’t figured out how to consistently deliver treatment that we know works to those most in need. “Instead, people are unnecessarily dying every day,” she said.

Unfortunately, simply knowing that clinics aren’t meeting the needs of TB patients doesn’t mean knowing how to fix the problem. In the past, well-intentioned outsiders have offered advice to clinicians on how to improve TB care, but these practices made sense in a different context. In rural South Africa, this counsel has yet to meaningfully improve outcomes for patients.

The Method

To address South Africa’s unique challenges, van de Water’s analysis of the health care system draws on techniques from implementation science, a field that she characterized as the study of “the uptake of evidence-based practices in regular everyday health care.

“This kind of research doesn’t take place in a highly controlled lab, but in the real world,” she explained. “It’s about understanding what makes it harder for something to be implemented, and what makes it easier.”

In other words, her subject is not tuberculosis itself but TB care: at what stages in the treatment process are patients failed, and what barriers keep them from getting the care they need?

About Tuberculosis (TB) in South Africa

450,000

# of South Africans who develop TB annually

89,000

# of South Africans who die from TB annually

53

% of South Africans who successfully complete TB treatment

To find out, van de Water and her team are using a strategy called the Systems Analysis and Improvement Approach (SAIA), which draws on data to map the stages in the treatment process where patients fail to progress to the next step. She will work with 16 facilities in the Sarah Baartman District of South Africa’s Eastern Cape to identify these bottlenecks. “Then, using micro-interventions or quality improvement projects, we help each clinic feel empowered to make improvements that they identify,” she said.

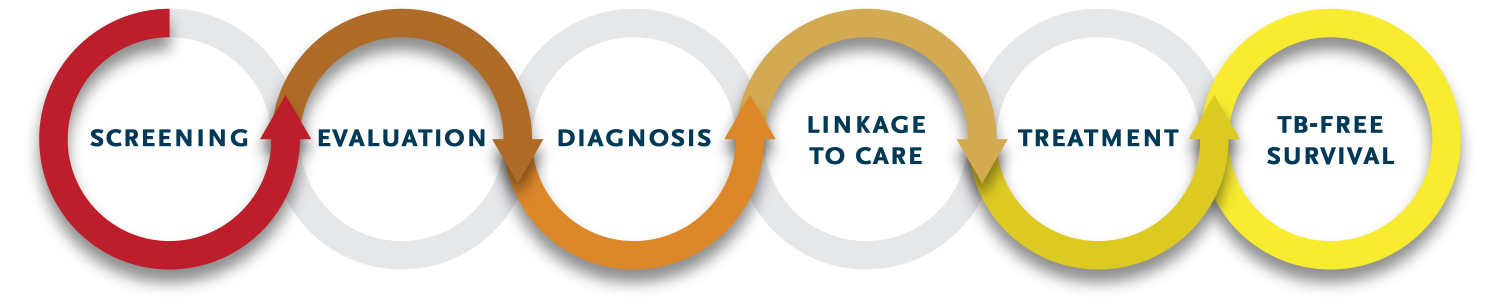

Van de Water and her team have identified six steps in the optimal “TB care cascade”: screening, evaluation, diagnosis, linkage to care, treatment, and tuberculosis-free survival. Each step represents a juncture in the treatment process where a patient might not progress—and an opportunity to rethink how each clinic operates. For example, one clinic may decide to screen all patients for TB, irrespective of symptoms, while another may work to alleviate local food insecurity.

Together with all 16 clinics, van de Water will implement what’s called a stepped wedge cluster randomized control trial. “Four clinics, or a cluster, start by implementing the project, which they’ll execute for 18 months,” van de Water explained. “The next cluster of four clinics starts three months after the first, and the next three months after that.” This design helps researchers zero in on variables in contexts where controlled experiments are impossible and allows the intervention to have the widest reach.

THE CARE CASCADE

The Research

This early in the study, van de Water has no idea yet which interventions will prove most successful. For her, that uncertainty is part of the appeal because it rewards openness to diverse ideas. “I think this work requires a lot of buy-in from district health officials and clinic staff,” she said. “We’re not coming in and taking over to run TB care for five years. Instead, each clinic can come up with micro-interventions that work for them.”

Brittney van de Water Photo: Sophie Smith

This chance to draw on the collective expertise and creativity of so many people is part of what most excites van de Water. Her role, as she sees it, is to support them in what they do by providing necessary analytics. “As the saying goes, if something doesn’t get measured, it doesn’t get managed—period,” she said. “That’s why we’re here: to coach, guide, and measure with people who are seeing firsthand what really works.”

In recognition of the importance of improving global tuberculosis care and the excellence of her research, van de Water recently received a Hood Foundation Grant for her ongoing work on TB and post-TB care for kids. This research, which will also take place in South Africa, is part of her broader effort to help transform a global health system that is failing vulnerable people. Ultimately, she believes it’s necessary to change the way wealthier countries think about global health so that more people appreciate the importance of preventable and treatable diseases like TB.

“I think that a lot of people in the U.S. think TB either doesn’t exist anymore or that we’ve fixed it or have a great vaccine for it,” van de Water said. “We haven’t, and we don’t. But we can provide evidence-based care for the people who need it the most if we choose to do the work and learn what really works. If we want to see a just system that offers universal access to care, it means starting with these fundamental basics of health care.”

STUDENT COLLABORATORS

Undergraduate research fellow Anna Laytham ’24 with Assistant Professor Brittney van de Water Photo: Sophie Smith

Key to van de Water’s research is the support of CSON students such as Anna Laytham ’24, an undergraduate research fellow who worked in South Africa this summer supporting the research team. “I was monitoring whether contacts were screened and, if they’d tested positive, getting treatment,” Laytham said. “It was amazing to see what research really looks like on the ground, and the realities of the barriers that people—both patients and researchers—really face. It’s just so important to understand the local context.”